The concept of the rights of man is one that I don't believe people in our country really understand anymore. The concept itself is critical to the nature of our government and it's operation. But ignorance of this, ingrained by modern humanism, and fear of it, for sounding "Laodicean", are it's enemies from the left and from the right. Because of these things, the point which is the very foundation of our government is undone. As the psalmist said:

Psa 11:3 If the foundations be destroyed, what can the righteous do?

I will attempt to reflect that which I read by Thomas Paine on this topic. He certainly is not the only founder to have something to say on it, and arguably he is not the most authoritative. But it is a starting point and he makes a good case.

In the days of the founders they had a task that few have ever had before them: to create a government from the ground up. They could have copied a more well known form from Europe- noone would've blamed them. They could have set up the Kingdom of America and elected Washington their first monarch. They could have instituted a Greek-style pure democracy. But instead they reasoned from the very beginning of humanity: what is government? What is the purpose of government? Who is government for and what are the best means whereby it's goals may be attained?

They began their reasoning like an engineer would begin analyzing a complex system, by looking at it's original state. Paine, though not a believing Christian, quickly turns to the Biblical creation account, at least as a point of history. From this he clearly notes "the unity of equality of man". He quotes the Creator, "Let us make man in our own image. In the image of God created he him; male and female created he them." He notes, there is no distinction between men and that this "...shows that the equality of man, so far from being a modern doctrine, is the oldest upon record."

Our modern, Christian-fear to discuss rights are addressed when he says: "By considering man in this light, and by instructing him to consider himself in this light, it places him in close connection with all his duties, whether to his Creator or to the creation, of which he is part; and it is only when he forgets his orgin, or, to use a more fashionable phrase, his birth and family, that he becomes dissolute [indifferent to moral restraints]."

My impression of modern Bible believers is that they fear to discuss having any rights because they don't want to be associated with the church of Laodice. This is as much an overreaction as fearing to talk about the Holy Spirit because of foolishness done in the charismatic churches. Like any other concept, we shouldn't fear to address it and frame it in a proper context and hold it in a proper balance: we should only fear holding it in imbalance, or holding to falsehoods or ignorance altogether. Paine implicitly addresses this by equally discussing duty- and specifically duty towards our Creator- in the same context. Duty is what balances a discussion of rights, for the "rights" we have from our Creator are given to us that we may serve him and each other, and not ourselves.

On another note, his observation about people becoming less moral when they forget their "origins" is prophetic! This statement was writtin in the 1790's, seventy years before Darwin published On the Origin of Species.

This really just introduces the topic and sets it in a right context. Knowning the short attention span of certain persons, I will cover the rest of this discussion in my next post.

Showing posts with label Half finished books. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Half finished books. Show all posts

Wednesday, September 23, 2009

Sunday, August 23, 2009

Mellowing out with Monty

Since Montesquieu has been less contentious, I'll post another smattering of his writings before returning to Paine and almost certain disagreement over his thoughts on 'natural rights'.

From Montesquieu, Book 3: 'Of the principles of the three kinds of government'

This statement needs some context. He is trying to explain what holds up a government (what he calls 'springs'), based on each type of government. Here, he is contrasting democracy with monarchy and despotism by highlighting it's most significant difference:

But in a popular state (republican), one spring more is necessary, namely, virtue.

Other statements:

When virtue is banished, ambition invades the minds of those who are disposed to receive it, and avarice possesses the whole community.

As virtue is necessary in a republic, and in a monarchy honor, so fear is necessary in a despotic government...

Fear must therefore depress their spirits, and extinguish even the least sense of ambition.

Montesquieu's observations about the requirement of 'virtue' (I think what we would now call character) for a successful republic are based on studies of Greek and Roman systems, which both eventually failed. This is very consistent with the thinking of a least some of the Founders:

We have no government armed with power capable of contending with human passions unbridled by morality and religion. Avarice, ambition, revenge, or gallantry, would break the strongest cords of our Constitution as a whale goes through a net. Our Constitution was made only for a religious and moral people. It is wholly inadequate for the government of any other. Letter to the Officers of the First Brigade of the Third Division of the Militia of Massachusetts (1798-10-11)

If Montesquieu and Adams are correct, then the most fundamental civic duty that anyone has is to both practice and to teach virtue/morals/character. As Christians, this is already part of our core mission, a.k.a. the great comission,; so Christians ought to be the most desirable of all citizens!

On the note of fear, both under Barry and under W, we have been constantly bombarded with messages of fear. Fear the terrorists, fear global warming, fear pandemics, fear economic collapse. It's not difficult to see that this is nothing but power grabbing by the Federal government. As noted by Monty, that type of leadership is a trademark of despotic rulership.

From Montesquieu, Book 3: 'Of the principles of the three kinds of government'

This statement needs some context. He is trying to explain what holds up a government (what he calls 'springs'), based on each type of government. Here, he is contrasting democracy with monarchy and despotism by highlighting it's most significant difference:

But in a popular state (republican), one spring more is necessary, namely, virtue.

Other statements:

When virtue is banished, ambition invades the minds of those who are disposed to receive it, and avarice possesses the whole community.

As virtue is necessary in a republic, and in a monarchy honor, so fear is necessary in a despotic government...

Fear must therefore depress their spirits, and extinguish even the least sense of ambition.

Montesquieu's observations about the requirement of 'virtue' (I think what we would now call character) for a successful republic are based on studies of Greek and Roman systems, which both eventually failed. This is very consistent with the thinking of a least some of the Founders:

We have no government armed with power capable of contending with human passions unbridled by morality and religion. Avarice, ambition, revenge, or gallantry, would break the strongest cords of our Constitution as a whale goes through a net. Our Constitution was made only for a religious and moral people. It is wholly inadequate for the government of any other. Letter to the Officers of the First Brigade of the Third Division of the Militia of Massachusetts (1798-10-11)

If Montesquieu and Adams are correct, then the most fundamental civic duty that anyone has is to both practice and to teach virtue/morals/character. As Christians, this is already part of our core mission, a.k.a. the great comission,; so Christians ought to be the most desirable of all citizens!

On the note of fear, both under Barry and under W, we have been constantly bombarded with messages of fear. Fear the terrorists, fear global warming, fear pandemics, fear economic collapse. It's not difficult to see that this is nothing but power grabbing by the Federal government. As noted by Monty, that type of leadership is a trademark of despotic rulership.

Labels:

Half finished books,

Montesquieu,

Political Thought

Thursday, August 20, 2009

Thomas Paine

Finally! My wife found the missing book tonight, so now I can post some of Thomas Paine's quotes from The Rights Of Man... that is, in between the crippling coughs...

Paine wrote this book largely in response to another work, Reflections On The Revolution In France by Edmund Burke. They are typically published as a single piece. Burke takes an ill view of the Frog's revolution while Paine ardently defends it. My own, very stunted, understanding of the French revolution has left me with the impression that it was a victory of unhalted humanism. It has been a great surprise to find out the details of this and to see it in an entirely new light.

Since this quote is a bit longer, I'll just post this one for the day:

It was not against Louis XVI, but against the despotic principles of the government, that the nation revolted. These principles had not their origin in him, but in the original establishment, many centuries back; and they were become too deeply rooted to be removed, and the Augean stable of parasites and plunderers too abominably filthy to be cleansed, by anything short of a complete and universal revolution.

When it becomes necessary to do a thing, the whole heart and soul should go into the measure, or not attempt it. That crisis was then arrived, and there remained no choice but to act with determined vigor, or not to act at all.

This one stuck out to me because he's basically saying the government was so broken, it was beyond repair and revolution was the only recourse. That gave me pause to consider our own circumstance! Have the parasites and plunderers so infected Washington that it is ill beyond all healing, or is it simply the most daunting task ever faced by our nation?

Paine wrote this book largely in response to another work, Reflections On The Revolution In France by Edmund Burke. They are typically published as a single piece. Burke takes an ill view of the Frog's revolution while Paine ardently defends it. My own, very stunted, understanding of the French revolution has left me with the impression that it was a victory of unhalted humanism. It has been a great surprise to find out the details of this and to see it in an entirely new light.

Since this quote is a bit longer, I'll just post this one for the day:

It was not against Louis XVI, but against the despotic principles of the government, that the nation revolted. These principles had not their origin in him, but in the original establishment, many centuries back; and they were become too deeply rooted to be removed, and the Augean stable of parasites and plunderers too abominably filthy to be cleansed, by anything short of a complete and universal revolution.

When it becomes necessary to do a thing, the whole heart and soul should go into the measure, or not attempt it. That crisis was then arrived, and there remained no choice but to act with determined vigor, or not to act at all.

This one stuck out to me because he's basically saying the government was so broken, it was beyond repair and revolution was the only recourse. That gave me pause to consider our own circumstance! Have the parasites and plunderers so infected Washington that it is ill beyond all healing, or is it simply the most daunting task ever faced by our nation?

Labels:

Half finished books,

Paine,

Political Thought

Thursday, July 30, 2009

Laws derived from the nature of government

From The Spirit Of Laws, Book 2

...indeed it is important to regulate in a republic, in what manner, by whom, to whom, and concerning what suffrages are to be given...

(a quote from Declam, 17 and18) Libanius says that at "Athens a stranger who intermeddled in the assemblies of the people was punished with death."

The constitutions of Rome and Athens were excellent- the decress of the senate had the force of laws for the space of a year, but did not become perpetual till they were ratified by the consent of the people.

...but in a republic, where a private citizen has obtained an exorbitant power, the abuse of this power is much greater, because the laws foresaw it not, and consequently made no provision against it.

But the most imperfect of all (types of aristocracies) is that in which the part of the people that obeys is in a state of civil servitude to those who command, as the artistocracy of Poland, where the peasants are slaves to the nobility.

The notion of interfering with domestic politics being a capital offense is rather novel. Surely with China and Arab nations, practical enemies to our way of life, owning so much of our national debt, we are at great risk to rule ourselves. We ought to at least cast off foreign debt!

I especially am fond of the idea that all laws ought to have a short expiration date, unless they are approved by the people. This brings them under constant review and keeps the policians busy digging holes and filling them up again. The actual idea behind this was to allow for a 'proving time' for laws, which is something we lack. They are hardly ever repealed, and then only with great effort. Gridlock is good.

Saturday, March 28, 2009

Truth and Error

Lately I have been reading The Rights of Man by Thomas Paine and ran across this tidbit:

“Ignorance is of a peculiar nature; once dispelled, it is impossible to re-establish it. It is not originally a thing of itself, but is only the absence of knowledge; and though man may be kept ignorant, he cannot be made ignorant.”

A couple of months ago, my beloved purchased a great book for the whole family to go through together called The Fallacy Detective. It was written by a couple of homeschool graduates and is focused on teaching children, from a Christian worldview, how to detect logical fallacies. It is really a book of short lessons, with lots of examples and age appropriate exercises. We have been going through it slowly, doing just a couple of lessons per week, and really trying to apply it. Neither my wife nor myself had ever received formal instruction in logic so this has been educational for us as well. On a day to day basis, we are seeing more and more fallacies enumerated in news articles, speeches, commercials and every day conversation.

A couple of months ago, my beloved purchased a great book for the whole family to go through together called The Fallacy Detective. It was written by a couple of homeschool graduates and is focused on teaching children, from a Christian worldview, how to detect logical fallacies. It is really a book of short lessons, with lots of examples and age appropriate exercises. We have been going through it slowly, doing just a couple of lessons per week, and really trying to apply it. Neither my wife nor myself had ever received formal instruction in logic so this has been educational for us as well. On a day to day basis, we are seeing more and more fallacies enumerated in news articles, speeches, commercials and every day conversation.

I present the quote above, regarding ignorance, because if there is a root cause to our current failures as a free nation, it is because people have cast off thought for feeling, reason for affections and truth for entertainment. This ignorance is the root cause of our rejection of God and toleration of those who push us further away from Him. This blot of darkness that pervades the public mind is the slave trader who will soon sell us to a new master. The best thing that free people can do, right now, is learn how to think and to educate others in the same.

One last thing, to preempt the friendly wounds of criticism that would say "Our mission is to preach the Gospel alone, and none other!", learning how to think orderly thoughts and instructing others in the same is no contradiction, or distraction, from preaching the Gospel of Christ. God is willing to reason with man, and it declared by Scripture that the Greeks seek after wisdom. While the foolishness of the Cross will never be reconciled to human wisdom, it is necessary for the Christian to employ Reason as a colaborer in our great commission, as Paul did at Mar's Hill. But how can a Christian do this if Reason is no friend of his? And how can it be received if the hearer has no capacity to understand truth? It would be like building a bridge where no room is found for footing on either end: possible only by suspending the entire span from the sky itself. Christian brothers, it is every bit in the best interest of filling our mission to both exercise ourselves and instruct others in the mode of proper thought.

“Ignorance is of a peculiar nature; once dispelled, it is impossible to re-establish it. It is not originally a thing of itself, but is only the absence of knowledge; and though man may be kept ignorant, he cannot be made ignorant.”

A couple of months ago, my beloved purchased a great book for the whole family to go through together called The Fallacy Detective. It was written by a couple of homeschool graduates and is focused on teaching children, from a Christian worldview, how to detect logical fallacies. It is really a book of short lessons, with lots of examples and age appropriate exercises. We have been going through it slowly, doing just a couple of lessons per week, and really trying to apply it. Neither my wife nor myself had ever received formal instruction in logic so this has been educational for us as well. On a day to day basis, we are seeing more and more fallacies enumerated in news articles, speeches, commercials and every day conversation.

A couple of months ago, my beloved purchased a great book for the whole family to go through together called The Fallacy Detective. It was written by a couple of homeschool graduates and is focused on teaching children, from a Christian worldview, how to detect logical fallacies. It is really a book of short lessons, with lots of examples and age appropriate exercises. We have been going through it slowly, doing just a couple of lessons per week, and really trying to apply it. Neither my wife nor myself had ever received formal instruction in logic so this has been educational for us as well. On a day to day basis, we are seeing more and more fallacies enumerated in news articles, speeches, commercials and every day conversation.I present the quote above, regarding ignorance, because if there is a root cause to our current failures as a free nation, it is because people have cast off thought for feeling, reason for affections and truth for entertainment. This ignorance is the root cause of our rejection of God and toleration of those who push us further away from Him. This blot of darkness that pervades the public mind is the slave trader who will soon sell us to a new master. The best thing that free people can do, right now, is learn how to think and to educate others in the same.

One last thing, to preempt the friendly wounds of criticism that would say "Our mission is to preach the Gospel alone, and none other!", learning how to think orderly thoughts and instructing others in the same is no contradiction, or distraction, from preaching the Gospel of Christ. God is willing to reason with man, and it declared by Scripture that the Greeks seek after wisdom. While the foolishness of the Cross will never be reconciled to human wisdom, it is necessary for the Christian to employ Reason as a colaborer in our great commission, as Paul did at Mar's Hill. But how can a Christian do this if Reason is no friend of his? And how can it be received if the hearer has no capacity to understand truth? It would be like building a bridge where no room is found for footing on either end: possible only by suspending the entire span from the sky itself. Christian brothers, it is every bit in the best interest of filling our mission to both exercise ourselves and instruct others in the mode of proper thought.

Sunday, March 1, 2009

How Christianity Changed The World

Finally, I finished this book. Here is my review.

This book is excellent: a must read for anyone interested in history, sociology or apologetics. It can be a foundation for any Christian seeking to understand "the big picture" and a guide for anyone wanting to unlock cultural secrets of the West to more effectively preach the gospel. The author consistently and directly tackles the question, "How has Christianity changed the world?"

The author establishes a benchmark for change in each chapter by contrasting early Christian views and practices with that of the surrounding world, chiefly the Greco-Roman system but also the Judaic and Semitic systems of the Middle East and, less often, the Far East systems. He then traces how Christ's followers impacted their world from a discipleship perspective and attempts to hit the highlights of change as they unfold in history to the modern age.

The first few chapters are by far the most impactful. The Christian ideas regarding respect for human life and women, health care and abolition were the most significant and often shocking to me. The high ideals held by and sacrifices made by Christians were in stark contrast to the very base and ignoble ideas of the Greco-Roman system- the same type of system we as a society are fast striving to rebuild. The middle of the book tackles important but less impactful ideas, specifically regarding government, economics and science. The end of the book was somewhat tedious, addressing architecture, music, literature, holidays and language; but he rigorously followed the same pattern and showed how much of our modern world still echoes the teaching of Christ.

The author is Lutheran and this slant definitely shows, but it never put me off. He equally embraces all mainstream Christian denominations without apparent partiality and constantly goes back to the Scriptures, to the teachings of Jesus and the acts of the early church. He favorably portrayed some people (such as Origen) and writings (Didache, Shepherd of Hermes) which I have been taught were the "bad guys" in some way or another, or were evil writings. This has caused me to question to some extent this clear-cut assumption. I may pursue further reading on some of these but it is really of little interest to me.

This book is excellent: a must read for anyone interested in history, sociology or apologetics. It can be a foundation for any Christian seeking to understand "the big picture" and a guide for anyone wanting to unlock cultural secrets of the West to more effectively preach the gospel. The author consistently and directly tackles the question, "How has Christianity changed the world?"

The author establishes a benchmark for change in each chapter by contrasting early Christian views and practices with that of the surrounding world, chiefly the Greco-Roman system but also the Judaic and Semitic systems of the Middle East and, less often, the Far East systems. He then traces how Christ's followers impacted their world from a discipleship perspective and attempts to hit the highlights of change as they unfold in history to the modern age.

The first few chapters are by far the most impactful. The Christian ideas regarding respect for human life and women, health care and abolition were the most significant and often shocking to me. The high ideals held by and sacrifices made by Christians were in stark contrast to the very base and ignoble ideas of the Greco-Roman system- the same type of system we as a society are fast striving to rebuild. The middle of the book tackles important but less impactful ideas, specifically regarding government, economics and science. The end of the book was somewhat tedious, addressing architecture, music, literature, holidays and language; but he rigorously followed the same pattern and showed how much of our modern world still echoes the teaching of Christ.

The author is Lutheran and this slant definitely shows, but it never put me off. He equally embraces all mainstream Christian denominations without apparent partiality and constantly goes back to the Scriptures, to the teachings of Jesus and the acts of the early church. He favorably portrayed some people (such as Origen) and writings (Didache, Shepherd of Hermes) which I have been taught were the "bad guys" in some way or another, or were evil writings. This has caused me to question to some extent this clear-cut assumption. I may pursue further reading on some of these but it is really of little interest to me.

Thursday, February 5, 2009

Concerning Christ and Jazz

For those who don't know, I am completely and utterly without the capacity to "do" music and, as a corollary, the ability to "appreciate" music. So I don't offer this so much to make a statement or even imply that I agree. Rather, I'm just poking a few people in the eye with it because deep down inside, I'm really immature.

Here's a quote from How Christianity Changed The World:

Richard Weaver, in his Ideas Have Consequences, saw this revolt even in the music of jazz., which, he said, gave the fullest freedom to the individual to "express himself as an egotist. Playing now becomes personal; the musician seizes a theme and improvises as he goes; he develops perhaps a personal idiom, for which he is admired. Instead of that strictness of form which had made the musician like the celebrant of a ceremony, we now have individualization.” Jazz, he argued, “has helped to destroy the concept of obscenity. By dissolving forms, it has left man free to move without reference, expressing dithyrambically whatever surges up from below. It is music not of dreams- certainly not of our metaphysical dream- but of drunkenness.” He further stated that the chief devotees of jazz are “the young, and those persons, fairly numerous, it would seem, who take pleasure in the thought of bringing down our civilization.”

Here's a quote from How Christianity Changed The World:

Richard Weaver, in his Ideas Have Consequences, saw this revolt even in the music of jazz., which, he said, gave the fullest freedom to the individual to "express himself as an egotist. Playing now becomes personal; the musician seizes a theme and improvises as he goes; he develops perhaps a personal idiom, for which he is admired. Instead of that strictness of form which had made the musician like the celebrant of a ceremony, we now have individualization.” Jazz, he argued, “has helped to destroy the concept of obscenity. By dissolving forms, it has left man free to move without reference, expressing dithyrambically whatever surges up from below. It is music not of dreams- certainly not of our metaphysical dream- but of drunkenness.” He further stated that the chief devotees of jazz are “the young, and those persons, fairly numerous, it would seem, who take pleasure in the thought of bringing down our civilization.”

Monday, July 7, 2008

The internet is boring

Today I'm baby sitting long running processes. It's not really that mentally engaging and normally I'll bring in a book when I have to do something like this because I can only take so much of the internet. I've got several good ones queued up at home- HG Wells' Outine of History, a couple of biographies on the founding fathers and an older Christian law journal with an excellent speech by John Adams in the 1840's (?) on the Constitution.

I'd really like to get a hold of a book called How Christianity Changed the World. This book analysis the differences between modern society and the ancient, greco-roman society that prevailed in the time of Chirst and attempts to explain how Christianity got us to where we are. I've read some excerpts and what I read was great. I love taking landscape looks at human history and then delving into details.

Lastly, I noticed that my pastor has a book on the history of race relations in KC. That would be a fascinating read as well.

Ah, this process just wrapped up. That's enough thinking about what I'd "like" to read of have "almost" read.

I'd really like to get a hold of a book called How Christianity Changed the World. This book analysis the differences between modern society and the ancient, greco-roman society that prevailed in the time of Chirst and attempts to explain how Christianity got us to where we are. I've read some excerpts and what I read was great. I love taking landscape looks at human history and then delving into details.

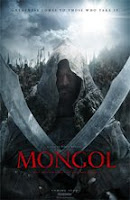

I've also wanted to read The Secret History of the Mongols for some time, but the times we've looked for it we haven't found it. It's the only historical document produced by the Mongolian empire and chronicles their rise under Genghis Khan. There's also an indie flick out called Mongol which looks freaking awesome!

I've also wanted to read The Secret History of the Mongols for some time, but the times we've looked for it we haven't found it. It's the only historical document produced by the Mongolian empire and chronicles their rise under Genghis Khan. There's also an indie flick out called Mongol which looks freaking awesome!

Lastly, I noticed that my pastor has a book on the history of race relations in KC. That would be a fascinating read as well.

Ah, this process just wrapped up. That's enough thinking about what I'd "like" to read of have "almost" read.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)